Happy Monday and welcome to my stop on the blog tour for THE SWALLOWTAIL LEGACY: WRECK AT ADA’S REEF by Michael D. Beil! I’m so excited to share an excerpt of the book with you today, AND more information about the author and tour, PLUS you can enter the giveaway to win a print copy!

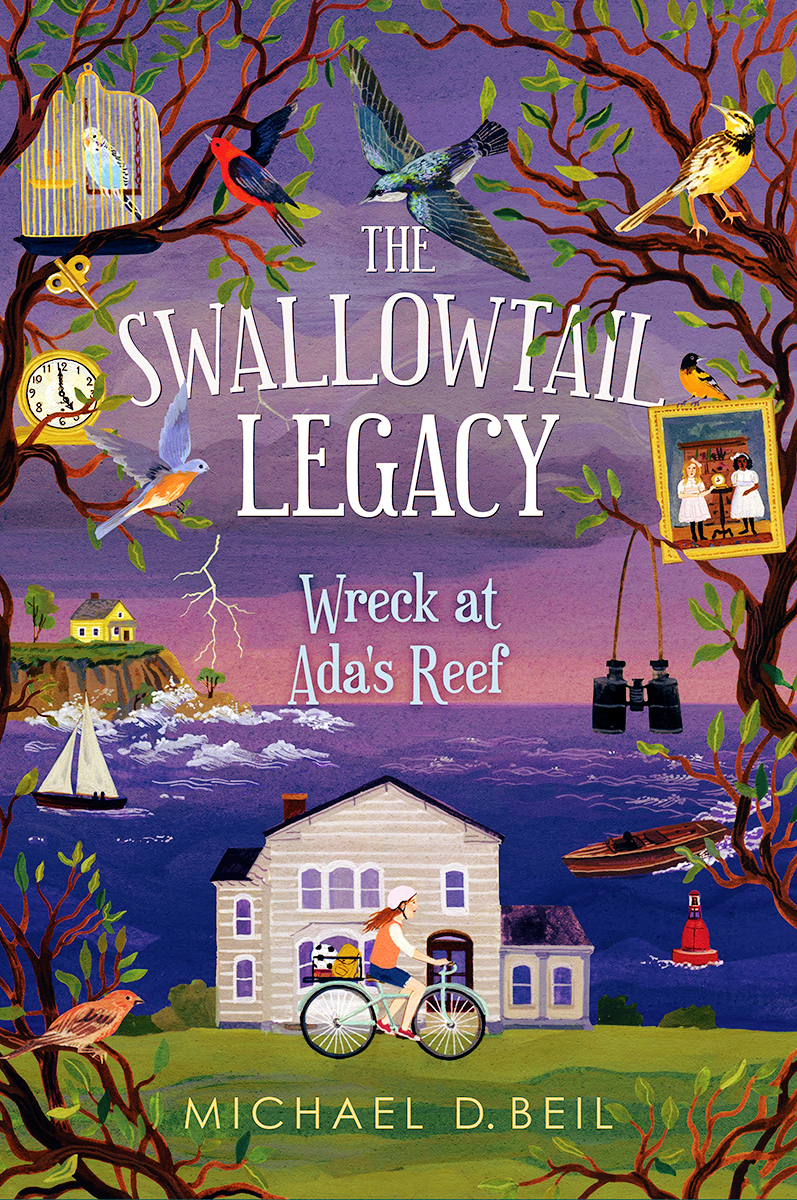

The Swallowtail Legacy: Wreck at Ada's Reef by Michael D. Beil

The Swallowtail Legacy: Wreck at Ada's Reef by Michael D. Beil Published on February 1, 2022 by Pixel+ink

Genres: Contemporary, Middle Grade, Mystery

Pages: 256

Add to Goodreads

Author Links: Website, Facebook, Goodreads, Amazon

Twelve-year-old Lark Heron-Finch is steeling herself to spend the summer on Swallowtail Island off the shores of Lake Erie. It's the first time that she and her sister will have seen the old house since their mom passed away. And while her stepfather and his boys are okay, the island's always been full of happy memories--and now everything is different.

When Nadine, a close family friend, tells Lark about a tragic boat accident that happened off the coast many years before, Lark's enthralled with the story. Nadine's working on a book about Dinah Purdy, Swallowtails's oldest resident who had a connection to the crash, and she's sure that the accident was not as it appeared. Impressed by Lark's keen eye, she hires her as her research assistant for the summer.

And then Lark discovers something amazing. Something that could change Dinah's life. Something linked to the crash and even to her own family's history with Swallowtail. But there are others on the island who would do anything to keep the truth buried in the watery depths of the past.

Chapter One

IT’S A DRIZZLY SUNDAY MORNING, the day after my twelfth birthday, and my family—such as it is—has arrived at Swallowtail Island in the western end of Lake Erie. All six of us stand on the foredeck of the ferry Niagara as it makes the turn at the buoy marked R3 at the entrance to the harbor. My ten-year-old sister Pip and I shiver in our thin cotton dresses, our arms pocked with goose bumps, as the town comes into view before us. Its two piers are like long arms reaching out into the harbor to greet us (Pip’s interpretation), or to push us away (mine). As the Niagara bullies its way down the narrow channel, its bow pushing a wall of water, the previously unruffled surface is pulled and stretched like gray taffy. Moored boats dance in our wake as we pass, bows and sterns rising and dipping with each wave. Near the east shore a fleet of mallards steams south toward a dilapidated wooden dock, and above me, a single gull cries, then swoops down to see if I have anything to offer it. Pogo, our English setter, “sets” beside me, body quivering and tail high in the air. I reach down and stroke the top of her head, but she doesn’t take her eyes off the gull for a second.

My heart leaps when we bump against the pilings at the ferry dock and lines are made fast: we have arrived. Without a word, Pip slips her tiny hand into mine; together our hearts pound out a rhythm that I am sure can be heard over the whining engine and shouts of dockhands.

Our stepfather, Thomas, gathers Pip and me along with his own three boys—Blake, Nate, and Jack—with his long arms. “Everybody ready? We should get a family picture. This is a big—”

“Let’s not,” I say. When I was five, and Pip three, our dad died when the small plane piloted by his best friend crashed into the Connecticut River a few hundred yards short of the runway at Goodspeed Airport. That same summer, Thomas’s wife was killed by a falling tree branch while she was jogging in Central Park. Four and half years later, Mom married Thomas. They had been friends (nothing more, they both insisted) in college and reconnected at a class reunion. So we had kind of a Brady Bunch thing going for a couple of years but then, three months ago, Mom died, and what was left? Thomas and his kids, and then Pip and me. I don’t know what we are, exactly, but it doesn’t feel quite like a family. “C’mon, Lark,” Pip says, squeezing my hand. “We should.” I am saved from the indignity of a family selfie there on the foredeck by one of the ferry’s crew: “Okay, folks. Need to ask you to move along.”

We wind our way down the steep metal staircase and onto the gangplank. When I reach the end, I hesitate before taking the final step onto the worn wood planks of the pier but there is, I know, no turning back. For the next seventy-two days (yes, I’m counting) this is home.

I’m not off the hook for that family portrait yet, though. Thomas has already recruited a woman in a yellow slicker to take our picture in front of a sign that announces “Welcome to Swallowtail Island” and is busy composing the shot. “Lark, since you’re the tallest, in the back with me and Blake.”

I grunt and move into my assigned place. Sometimes it is easier just to do what Thomas wants and get it over with. The woman in yellow says, “Smile!” and I do my best to provide something that at least resembles one. My teeth are clearly visible, so that counts, right?

With that little bit of torture out of the way, the other five of us leave Blake, not quite fourteen, in charge of our bags and the cage holding my budgie, Bedlam, and trudge toward town to get our bearings and to find a ride to the house that has been in our family since the 1920s, and where Mom spent her summers as a kid. The last time I was here was the summer I turned ten, the same summer that Mom first got sick. After that, it was like someone hit pause on our lives. For the next two years, the only traveling we did was on I-95 between Connecticut and Lenox Hill Hospital in New York.

It was a lawyer who pressed play, calling us into his office the week after Mom died to tell Pip and me that the house on Swallowtail Island now belonged to the two of us.

***

As we amble along Main Street, strangers in a strange (and strangely quiet) land, a light, ground-hugging fog filters out the town’s imperfections—the peeling paint, the cracked and frost heaved sidewalks, the shuttered storefronts—making it appear more charming than I remembered it to be. Slowly, though, the fog lifts higher and higher, until it hovers just above the treetops, and the sun begins to peek between the maple branches, highlighting Swallowtail’s blemishes in a golden glow. But who am I to call out its flaws? I mean, it’s not like I’m perfect—ask anyone. When Thomas first told us that we were going to spend the summer on Swallowtail Island, it was his idea that I start keeping a journal, to help me deal with “my issues.” He first brought it up when Mom got sick but I wanted nothing to do with it. “Trust me,” I said. “You really don’t want to know what I’m thinking most of the time.”

“It’s not for me,” he said. “It’s for you. I’m not going to read it. You’re right—I don’t want to know what you’re thinking. But it’s good for you to know, and sometimes the only way to do that is to write it down.”

“What’s supposed to go in it?” I asked.

“Whatever you want. What you’d like to say out loud but don’t—that is, if there is anything that fits in that category. You’re a very observant person. Unusually so, I’d say. But you’re so much more than a mere observer. You’re constantly gathering and analyzing data, plugging it into your own formula of how the world works. You’re a born scientist. On top of that, you have a baloney detector that would make Holden Caulfield proud. So, observe. Gather. Rant. Draw pictures if you want. There’s no rules unless you make them. Marcus Aurelius wrote in the morning.

Seneca did it at night.” Thus began the unvarnished journal of Meadowlark Elizabeth Heron Finch. I know, right? Twenty-nine letters, not counting that hyphen. (“A perch for the two birds,” Mom explained.) My sister’s is almost as bad: Sandpiper Alanna Heron-Finch. When my mom, Kate Heron, met my dad, Marc Finch, they decided that the bird thing was fate, so when we came along, they “had no choice” but to keep the ball rolling. By the way, no one calls us by our real names, ever. I’m Lark and she’s Piper or, most of the time, just Pip.

For the moment, there’s only one rule when it comes to my story: I promise to be honest. Otherwise, what’s the point? But I should probably clarify: Just because I promise not to lie doesn’t mean that I’m going to tell the entire truth. I’m not one of those people who is determined to share every unspoken thought with the world and I don’t want to be. Here’s the God’s Honest Truth about me: There are places in my own brain that, when I make a wrong turn and accidentally end up there, I turn around and get out as fast as I can. No need to go poking around places like that—who knows what I’ll find.

***

Further west on Main Street, the town starts to perk up. No cars or motorcycles are allowed on the island, so it’s not unusual to see horses and buggies sharing the road with electric golf carts and bicycles. To Pip, who has taken riding lessons at a stable in Chester for the past two years, horses are the best thing about the island. She loves them beyond all reason, and once prepared a PowerPoint presentation to convince Thomas to buy her one. I think they’re very pretty, but the GHT (God’s Honest Truth) is that I can do without them. A twenty-year old palomino tossed me out of the saddle at summer camp a few years ago, and I swear he looked back and laughed at me when I hit the ground. And seriously, have you seen those teeth? I’ll take a bicycle, thank you very much.

We stop in front of the old-fashioned drugstore where we arrange for a wagon to take all of us and our stuff to the house. The boys go inside with their dad while Pip and I stay out on the sidewalk. She wanders a few doors down to pet a horse that is harnessed to a small, Amish-style buggy while I peek through the front window at a stack of the local weekly newspaper, the Swallowtail Citizen. The headline reads “Tragedy Strikes Swallowtail 75 Years Ago,” and next to it is a grainy black-and-white photo that takes up the top right quarter of the page. It shows the wrecked hull of an old-school wooden speedboat—like something from an old movie. There are several ragged holes across the bottom of the boat, the largest a good three feet long. Not all of the article is visible through the glass, but I’m able to read enough to learn that the writer is convinced that the speedboat crash that killed Albert Pritchard was no accident and that it was probably also connected to the death of the town’s most important citizen, Captain Edward Cheever. Pritchard was Cheever’s lawyer, and was returning from visiting friends in Leamington, Ontario, when he plowed into the rocks known as Ada’s Reef just west of Swallowtail Island. When I’ve read as far as I can through the drugstore window, I go back to the top where I see that the article was written by Nadine Pritchard—Mom’s oldest friend and the main character in just about every story from her childhood.

“Pip, you have any money on you?” I ask. “I need fifty cents for a paper.”

“What? No. It’s back in my bag. Come and look at this horse. Isn’t he beautiful?”

“Yeah, he’s great,” I say, handing her Pogo’s leash. “Hold Pogo for a sec. I’m going inside. Don’t go anywhere.”

Thomas is on his way out the door as I open it. “We’re all set,” he says. “The wagon’ll be here in a few minutes. Supposedly.

Where’s Pip?”

I nod in her direction.

“Oh, right. Horses.”

“Can I borrow fifty cents?”

“Sure.” As he digs two quarters out of his pocket and holds them out, I realize he already has a copy of the newspaper in his other hand.

“Oh. You already . . . that’s what I was gonna buy.” He hands me the paper, along with a five-dollar bill. “Get some drinks for you and Pip. This may take a while. Remember the last time? The guy showed up an hour late and then he blamed us. Said we were in the wrong place.”

Thomas is right. Everything on Swallowtail Island takes a while. Our house is only a couple of miles from the drugstore, but by the time we pick up Blake and the bags and clippity-clop our way there, winding through the streets of downtown and then north on the unpaved Captain’s Road, a good hour has passed. I don’t mind; the sky has cleared up and I’m lying back with my head on my duffel, reading the rest of Nadine’s story about the speedboat crash and ignoring the locals who stop to watch us go by, some of them shaking their heads and muttering about “summer people.”

Shortly after we pass the protected cove known to the locals as “the little harbor,” we come to a fork in the road.

“That’s our house!” Pip cries, pulling me up by the arm to make me look at the carved wooden sign pointing to “The Roost.”

The driver makes the turn and we wind down a long, dusty drive bordered by cornflowers and Queen Anne’s lace with Pip still gripping my arm and vibrating with excitement. As for me, I’m acting nonchalant, but inside I have to admit that I’m incredibly curious if nothing else. I can’t deny that I still haven’t wrapped my head around the idea that the Roost actually belongs to Pip and me, and no one else. It sounds like something from an old novel.

Around one final bend, and the house and barn come into view.

“Here we are,” the driver says, making a wide turn in the yard.

We’re still moving, but Pip stands, so now it’s my turn to hold her arm so she doesn’t do a face-plant into the dirt. Her mouth falls open, and she shakes her head in disbelief. “It’s so beautiful! It seems like forever since we were here.” Sometimes two years is forever.

The house has definitely suffered a bit from neglect in the two years since our last visit, not that it was in perfect condition then. It’s kind of New England-y looking, like our house in Connecticut, except that the Roost’s siding and trim are badly in need of a paint job, and quite a few shingles are either missing or crooked. But the yard is neat and freshly mowed, and somebody has trimmed the shrubs around the house. With the exception of a couple of broken windowpanes, the barn—classic red with a gambrel roof, and surrounded by a good-sized fenced pasture—is in excellent condition.

The wagon shudders to a stop and all five of us kids (and Pogo) hop off, ready to explore, when Thomas predictably holds up a hand. “Wait. Everybody stop right where you are. Let’s get the bags off the wagon and then . . . we need a picture.”

Five groans. Maybe six—I swear Pogo joined in. She is ready to chase something—anything.

“Man,” I say, hanging my head. “You’re killing me.” He grins and lines us up with the house in the background. The wagon driver takes the picture, then climbs back aboard and waves goodbye. “Give me a call if you need a ride anywhere,” he says. “Number’s on the card.”

Thomas thanks him, then says, “Now, maybe one of just Lark and Pip. It is their house, after all. The rest of us are their guests.”

“Can I be opening the door?” Pip asks. “Where’s the key?” “Here you go,” says Thomas, tossing her a red rabbit’s foot with one brass key dangling from the chain.

She opens the door and then assumes a car show–model pose, pointing to the opening as a small bird flies out, missing her head by inches. Pip holds a hand to her heart. “Omigosh. That scared me!”

“Are you done?” I ask Thomas, so flustered by the bird that he drops his phone.

“He probably came down the chimney,” he says. “Your mom mentioned something about that. Anyway, I got the picture, so we can go inside.”

“Probably a swallow,” Pip suggests as we crowd through the narrow door. “The island’s named after them, there’s so many here. I think it’s a sign that we’re going to have a great summer.”

“‘One swallow does not make a summer, neither does one fine day,’” says Thomas, mysteriously. We all ignore him as we do whenever he says something strange, so he adds, “Aristotle said that.”

Goody for him, I think.

“It’s a good thing we got here when we did,” says Jack, eight, the youngest. “That poor bird would have starved to death.” Jack worries about things like that. He’s the kind of kid who shoos ants out of the house instead of killing them. “Are you sure it wasn’t a bat?” asks Nate, who is two days older than Pip, a difference that he never lets her forget. “I hate bats.”

I set the newspaper and my backpack on the kitchen table. “It wasn’t a bat. They only come out at night . . . when they turn into vampires.” I whisper into his ear: “And go searching for the blood of little boys. Especially little boys with brown eyes and curly hair.”

Pip stands in the middle of the kitchen, hugging herself as she takes in the whole scene. “It’s exactly the way I remember it.” She runs to the hallway closet, opens the door, and then points at pencil marks on the wood trim inside with a squeal. “They’re still here!”

“Why wouldn’t they be?” I ask. “You think someone’s going to break in here and erase them?”

“I know, but it’s Mommy! Katie, age five! She was so little! Here she is at ten, the same as me.” She backs up against the wall and looks at me. “Who’s taller?”

I lean in for a closer look. “Looks like a tie.”

“No, it’s not,” says Blake. “Pip’s—”

“Exactly the same height,” Thomas cuts him off with a wink.

Blake takes the hint. “Oh . . . yeah. You’re right.” Pip’s face lights up even brighter. “And then she grew all the way to . . . here! Do you think I will, too?”

“Definitely,” I say as I wander through the kitchen door into the wallpapered dining room and through that into the living room—my living room, I think to myself. A wide staircase divides the rest of the downstairs into two large rooms, the “official” living room with its stiff, rather dated furniture, and the room that Mom called the bird room, with walls of book shelves and a small loft (reached by a ladder) in the bay that juts out toward the lake. (This might be the place to say that Mom, no doubt inspired by the family name, became a professor of ornithology at a university that everyone has heard of.) Anyway, the reason it’s called the bird room is obvious: Resting on tables and shelves, hanging from wires, perched on curtain rods, sitting on the molding above doors and windows, and everywhere else you look are birds of every shape and size. A life-sized great blue heron in bronze anchors one end of the fireplace mantel, at the other is a mounted tree branch with a variety of carved and brightly painted finches (a gift from Dad to Mom on their wedding day).

Something about not seeing the house and especially this room full of memories for a couple of years gets to me. I feel my legs getting a little wobbly, so I settle into a chair before I do a face-plant onto the hardwood. Pip and the boys are running around—why are they screaming, anyway?—but I stay in the chair for a long time, composing myself.

Eventually, Thomas finds his way to the bird room. “There you are. I wondered . . . are you okay? You look a little peaked.”

“What? I’m fine,” I say, almost believing it myself. “Oh. Geez. This room . . . I’d forgotten . . .” He looks a little weak in the knees, too, and he steadies himself with one hand on the mantel. He reaches up with his other hand and runs it down the neck of the bronze heron, turning his face away from me. When his shoulders start to tremble, I feel like I’m intruding on a private moment and decide to busy myself by airing out the room. I head to the far end of the room, where I push aside the curtains and turn the cranks to open the windows wide. As a faint breeze begins to replace the stuffy, stale air, Thomas wipes his eyes and forces a smile.

“Good idea,” he says. “Let’s open all of them. Then everybody out to the front yard.”

I grab Bedlam’s cage from the kitchen and race up the stairs, taking a sharp left into the room that Pip and I share. Both upstairs bedrooms have views of the lake, but the one on the left is smaller and has a pair of matching twin beds, while the one on the right has two sets of bunk beds for the three boys. Pip, a step behind me, runs straight to the French doors that take up much of the front wall and throws them open. Her hands cup her face as she steps out onto the narrow balcony that runs the width of the room and looks out at the western end of Lake Erie, letting the wind tousle her hair. “I feel like I’m dreaming. It’s too perfect. I’m afraid I’m going to wake up and it’ll all be gone.”

I set Bedlam on an end table and pinch Pip gently on the arm. “There. See? It’s real. It is weird. . . . I mean, it feels like—”

“—like home? For me, too!”

“I was going to say that it feels like, I don’t know, when I walked in here I almost expected to see Mom there on the bed, sitting up with a book on her lap. It’s stupid.”

Pip launches herself at me, throwing her arms around my neck. “It’s not stupid. Don’t say that. She is here . . . kind of. This was her room when she was a little girl. And remember, she used to say she thought it was haunted. Maybe—”

“OUT-RAAA-GEOUS!” Bedlam cries. It’s his favorite word.

“I agree with Beddie,” I say. “Mom was teasing us. There’s no such thing as ghosts. So, which bed do you want this year?” The two beds are identical, with white-painted headboards and footboards, but every summer we came to the island, I gave Pip first choice. Most kids would probably pick one side and stick with it, but not Pip. And she always had a very specific reason for her choice. Two years ago, she picked the one on the right because she insisted that it was better for viewing the moon.

She spins, twisting her lips as she considers this Very Important Decision. She raises an index finger slowly, moving back and forth between the two before stopping at the bed on the left. “That one.”

“You’re sure.” I look up to admire the mobile that the wind from the open doors has set in motion. Not surprisingly, it’s made up of eight different species of birds, all with wings extended as if they’re flying.

“Ummm . . . yes. Positively. My Misty poster is going right here next to me. And I can keep my books on the table.” Pip has all of Marguerite Henry’s Misty of Chincoteague books, and has read each one at least a hundred times. When I suggested that perhaps she didn’t need to bring them all with her—after all, we’re just staying for the summer, I said—she looked at me as if I’d grown a second head.

“Girls!” shouts Thomas from the front yard. “Come on down!”

Pip waves at him from the balcony. “Can we stay here forever?” “How about we have some lunch and talk about that later,” answers Thomas. When we come out the sliding glass door at the front of the house, he is sitting on a plaid blanket in the front yard, unpacking a cooler packed with sandwiches and cans of soda. “Turkey on the left, ham on the right. Everyone grab and go. Lark, will you open that bag of chips, please?” “What kind of soda is there?” asks Jack, excited because he usually isn’t allowed to drink it.

“Any flavor you like . . . as long as it’s orange,” says Thomas. “If you don’t like it, blame Nate—he picked it out yesterday. By the way, people out here don’t call it soda. It’s pop.” The way he says it sounds like paaap.

Jack looks at him as if he thinks his leg is being pulled. “You’re teasing.”

Thomas holds up a hand. “Ask Lark.”

When Jack looks to me for confirmation, I nod. “He’s right, Jack. You don’t remember, ’cause you were so little the last time you were here. Wait till you meet some of the local kids. They all have a funny accent.” I choose a turkey sandwich and sit on the low brick wall at the front edge of the property. The Roost sits high up on a rocky point of land above the lake, and directly below me, small waves break on a narrow beach that is strewn with driftwood and seaweed.

Jack joins me on the wall and holds out his hands. “Kate used to hold on to me so I could look out over the edge.” I set my sandwich down and grip his wrists tightly. “You okay? I can’t believe Mom let you do this when you were six years old.”

“It’s not that scary,” said Jack. “Dad! Can I go down to the beach?”

“Not now,” says Thomas. “You’ll have plenty of time for that later. We have lots to do today. We need to unpack, and make beds, and figure out what we’re going to eat. I’ll ride into town for a little shopping, assuming that the bikes are still in the barn. And the tire pump. Volunteers to join me?”

“I’ll go!” Jack says.

“I appreciate the offer, Jack, but it’s a long ride,” Thomas says. “Why don’t you stick around and explore the house? Blake, how about it?”

Blake mumbles, “All right, I’ll go,” through a mouthful of sandwich.

“Great. Thank you,” says Thomas. “You can pick what you want for dinner.”

“Gee, I wonder what that will be,” I say, knowing full well that it’s going to be chicken of some kind. Blake would eat chicken every meal of every day if he could. I swear the kid’s growing feathers.

“Whose house is that?” Jack asks, pointing to the beautiful— and enormous—Victorian cottage half a mile north, perched on a rocky cliff much higher than the one we’re standing on. “It’s like a mansion.”

“Some sea captain,” I say. “It’s a museum now.”

“Not just any sea captain,” says an unfamiliar voice. “Captain Edward Cheever.”

We all spin around to find a man in starched khaki pants and a matching safari shirt with its short sleeves rolled right to his shoulders, the better to show off his impressive biceps and tattoos on both forearms. His steel-gray hair is cropped short and perfectly flat on top, as if it were done with a lawn mower—and he looks hard-boiled enough that it just might have been. I have a vague memory of seeing him before. It must have been three or four summers back, before Mom and Thomas got married, when he stopped by the house after a bad storm to see if we were okay. Just like that time, he seems to have just appeared out of thin air—none of us saw him coming and then there he is, standing three feet away. The only thing missing is the puff of smoke.

“Sorry, didn’t mean to scare you,” he says in response to our blank stares and open mouths. He approaches Thomas and as they shake hands, Thomas winces a little. “Don’t know if you remember me. Les Findlay. Live down the road a bit. Saw you pass by and thought I’d stop and say hi.”

“Right. Les. I’m Thomas. Emmery. Sure, I remember you. Good to see you again. Been a couple of years.”

“Miss Pritchard told me you were coming. Told me about Kate. A real shame. My condolences. Always liked her. Anyway, Miss Pritchard asked me to get everything ready for you. Said you were planning to spend the summer.”

“She was Mommy’s best friend when they were kids,” Pip says. “She’s at a horse show—that’s why she didn’t meet us at the ferry.”

“Coming back on the last boat tonight, I believe,” says Les. With a nod at the folded copy of the Citizen on the blanket, he adds, “I see you’re catching up on all the local news. That’s quite a story Miss Pritchard spins.”

I lift the paper and point to the picture of the destroyed boat. “The man who got killed—was he related to Nadine? She doesn’t say, but he has the same last name.”

“Sure is—was. Albert Pritchard was her grandfather.”

Thomas looks over my shoulder at the front page of the paper. “Wow. That must have been some crash.” Findlay points to the house we’d been looking at when he mysteriously appeared. “Look to the left of the museum, couple of hundred yards. See that buoy? That’s where the wreck happened. Ada’s Reef, it’s called. Named after Captain Cheever’s daughter. Or maybe his daughter was named after it—I forget. Nasty rocks a few inches below the surface. Pritchard’s boat was fast, a double-cockpit Hacker, nineteen forty. He was probably going fifty when he hit ’em.”

Sunlight is sparkling on the water, and I squint for a better look at the buoy. “The buoy has a light on it, right?” I say. “A red one.”

“That’s right. Flashes every second.”

I let that sink in. “Was it—the light—there when the crash happened?”

Findlay nods, and the corners of his mouth turn up ever so slightly. “I see where you’re going. Folks’ve been asking that question since the night of the crash: What was he doing on the wrong side of that buoy on a calm night? He knew the waters around the island like the back of his hand. Don’t make sense.”

“I guess that’s why it’s still selling newspapers,” says Thomas. “People love a good mystery. Lark here is really good at solving them.”

As Les Findlay talks, Jack zeroes in on his tattoos and follows every movement of those muscular forearms. Eventually, he works up the courage to ask, “Were you in the navy or something? Is that why you have a tattoo of a ship?”

Findlay holds out his right arm for all of us to see. “It’s not a ship. It’s a PBR—a kind of patrol boat. I took one up the Mekong River in Vietnam back in sixty-seven, sixty-eight. Funny thing is, when I left there, I swore I’d never set foot on another boat. Said I was gonna move to Montana, as far from the water as I could find. But here I am living on an island and runnin’ a work boat—even kinda looks like the PBR. Only difference, most days nobody’s shooting at me. I work down the marina, sorta semi-retired now. Life’s funny, I guess.” He pauses, looking as if he has something to add, but gives up with a shake of his head. “I’ll leave you folks to your lunch now. You need anything, you know where to find me.”

Actually, I’m thinking, We don’t—“down the road a bit” isn’t exactly precise now, is it?

Findlay tips an imaginary cap and disappears into the brush as quickly and as silently as he’d appeared.

“Most days?” I say when he’s out of sight.

“What do you mean?” Thomas asks.

“What he said. Most days nobody’s shooting at him. So, like, some days they are?” Maybe Swallowtail Island isn’t as peaceful as it seems.

Week One

| 2/7/2022 | Pick A Good Book | Review/IG Post |

| 2/7/2022 | The Reading Wordsmith | Review/IG Post |

| 2/8/2022 | YABooksCentral | Excerpt |

| 2/8/2022 | Kait Plus Books | Excerpt |

| 2/9/2022 | Nonbinary Knight Reads | Review/IG Post |

| 2/9/2022 | Girls in White Dresses | Review |

| 2/10/2022 | Little Red Reads | Review |

| 2/10/2022 | @jypsylynn | Review/IG Post |

| 2/11/2022 | Eye-Rolling Demigod’s Book Blog | Review/IG Post |

| 2/11/2022 | The Bookwyrm’s Den | Review/IG Post |

Week Two

| 2/14/2022 | Rajiv’s Reviews | Review/IG Post |

| 2/14/2022 | OneMoreExclamation | Review/IG Post |

| 2/15/2022 | Nerdophiles | Review |

| 2/15/2022 | @coffeesipsandreads | Review/IG Post |

| 2/16/2022 | The Momma Spot | Review/IG Post |

| 2/16/2022 | BookHounds YA | Review |

| 2/17/2022 | Lifestyle of Me | Review |

| 2/17/2022 | @enjoyingbooksagain | Review/IG Post |

| 2/18/2022 | Two Points of Interest | Review |

| 2/18/2022 | Locks, Hooks and Books | Review |

Enter here to win a print copy of The Swallowtail Legacy: Wreck at Ada’s Reef by Michael D. Beil!

(US Only)

What do you think about The Swallowtail Legacy: Wreck at Ada’s Reef? Have you added it to your tbr yet? Let me know in the comments and have a splendiferous day!

Cute cover